NEWS RELEASE – Aug. 12, 2024

Retired Beckley ARH Hospital employee was a participant in medical history

BECKLEY, W.Va. – John Ellison knows his childhood wasn’t much different from that of most anyone growing up in the coalfields of southern West Virginia during and immediately after the Great Depression.

“My dad worked in the mines and mom was a housewife,” said Ellison, the sixth of nine siblings. “We always had a big garden and a cow and my mom would can enough that you’d be able to eat from one summer to the next.

“We were poor people but everybody else was poor, too.”

And like many at 19, Ellison wasn’t exactly sure what he wanted to do with the rest of his life. All he did know, he said, was that he didn’t want to follow his father underground.

It’s not unusual today to hear of someone heading south in search of work. In 1952, however, most went north.

“So, a friend and I went to Cleveland to work for a General Motors plant,” Ellison recalled.

He said it was good work, too, but less than a year later, in early 1953, he was drafted into the Army to serve in the Korean War.

The war ended while Ellison was still in basic training in Colorado – learning to ski and snowshoe in preparation for harsh Korean winters.

When he was eventually discharged from the military, he returned home to Beckley and to an uncertain future.

Ellison still had no intention of working in the mines, but employment at a new hospital designed to serve miners and their families piqued his interest.

His first attempt at employment was a miss as other likeminded jobseekers formed a line that he said stretched from the front door, through the parking lot and well down the main road.

Soon, however, an acquaintance who worked for the local UMWA office reached out to see if he might be interested in working as an orderly (nurses’ aid).

“I kind of laughed and said I didn’t know anything about it but told her I’d give it a try,” he said.

It was a decision that would shape every aspect – both professionally and personally – of his life.

And though Ellison had no interest in becoming a coal miner himself, he was on the frontlines of an effort that has helped millions of miners in the years since.

***

Ellison was on shift Jan. 4, 1956, the day former UMWA President John Lewis, along with other dignitaries including former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, visited Beckley to dedicate the 10 original Miners Memorial Hospitals (known today as Appalachian Regional Healthcare or ARH).

So was his wife Sally, who traveled from her native New York to Beckley after reading a job posting for the hospital in a nursing magazine.

“I remember it said LPNs would make $98 every two weeks and that was a lot of money,” Sally recalled. “I was 20 years old and had never been away from home but here I am.”

The couple married in 1957, and Sally left the hospital a few years later to raise their two children and work for the board of education.

Ellison, however, said he knew he was at the hospital for the long haul.

“I started as an aid, but I had a friend doing EKGs and he wore a white coat and dress pants, and I thought, ‘now there’s a job I’d like,’” he said.

When a position opened up a few years later, Ellison got his wish.

He recalls working with former Chief of Medicine Dr. Albert Kisten, a cardiologist who Ellison said was “way ahead of his time.”

“He’s the one who first taught CPR at the hospital,” he recalled. “He set up mannequins in the lab and doctors and nurses would come in on Saturdays so he could train them.”

“He’s the one who first taught CPR at the hospital,” he recalled. “He set up mannequins in the lab and doctors and nurses would come in on Saturdays so he could train them.”

Ellison was in the room for what he believes was West Virginia’s first pacemaker implantation.

“I had never seen a chest opened up or a heart exposed,” he said. “And I was part of it doing threshold checks to make sure the pacing was right.

“That was really exciting to be part of.”

***

Ellison continued as an EKG tech throughout his career, but soon took on a new role as well.

It was around the time of the first pacemaker procedure when Dr. Donald Rasmussen began working at the hospital as associate chief of medicine.

Ellison said the Colorado native had been drawn to the coalfields because of studies he had read about the effects of coal dust on the lungs of miners.

“He wondered why nothing was being done to help them,” Ellison recalled. “But he needed proof.”

So, Rasmussen got to work, establishing a black lung pulmonary lab.

Ellison explained how miners thought to have been affected by coal dust, underwent a series of testing during which their breathing and bloodwork were studied before and after exercising on a treadmill.

“I was responsible for running the arterial blood gases and another tech, Ralph Sutphin was in charge of the pulmonary function test,” Ellison explained of his role as chief pulmonary lab technician working alongside the late Sutphin.

Ellison said they often found that the blood oxygen levels of afflicted miners would initially register as normal but would plummet during and after exertion.

As Rasmussen worked in the lab, two other physicians, Dr. Hawley Wells and Dr. I.E. Buff, used his results to rally politicians and miners in an effort to push for legislation to protect and compensate those affected.

“They used our test results to rattle the cages until they finally got the legislation passed,” Ellison said.

With legislation in place, Rasmussen – with Ellison and Sutphin by his side – continued to run the pulmonary lab.

“Miners need proof of black lung before they can be compensated,” Ellison said. “So, that’s what we did.”

***

Ellison retired from full-time work at Beckley ARH in the 1990s but continued to help in the lab part-time for a few more years before stepping away completely.

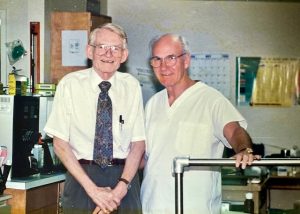

Though the men no longer worked together, Ellison said he and Rasmussen maintained a strong relationship.

Though the men no longer worked together, Ellison said he and Rasmussen maintained a strong relationship.

“Dr. Rasmussen was disabled in later years and couldn’t drive so I’d pick him up every day for about 10 years and take him to the lab,” Ellison said. “We’d have coffee and chat for a half hour or an hour until his patients came in.

“He was my boss, but he was a friend,” he continued. “He was a good friend.”

Ellison, now 92, is in good health, but recently benefitted from that same groundbreaking procedure he assisted with more than 60 years ago.

“I had to have a pacemaker,” he said, laughing as he thought back to that first pacemaker procedure in 1962. “The patient was 74 and I remember thinking she was an old woman.

“Now I know 74 is certainly not old.”

Ellison and Sally have one grandchild – they lost a second grandchild in a car accident several years ago – two step-grandchildren and one great-grandchild.

They are active members of Grove Christian Church in Beckley, and Ellison keeps busy working part-time as a funeral attendant for Melton Mortuary.

He believes he and Sally are among just a handful of surviving original Beckley Miners Memorial Hospital employees.

Rasmussen, who, in 1969 received the American Public Health Association’s Presidential Award for his black lung work, continued in private practice in Beckley until just before he passed away in 2015.

Upon Rasmussen’s death, James Green, professor emeritus of history at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and the author of “The Devil Is in These Hills,” told the New York Times, “In the annals of American labor history, there is no one, no union official or a physician, who exceeds the accomplishments of Dr. Rasmussen in substantially reducing the causes of such a widespread and deadly disease as black lung or in enhancing the treatment of a group of afflicted workers.”

Ellison has always known the importance of Rasmussen’s work but has only recently begun to consider his own contributions to the effort.

“None of that work happens without Dr. Rasmussen, but I was there,” he said. “Ralph Sutphin was there. We were part of that, too.

“We did a lot of important things,” he continued. I don’t think people give BARH (Beckley ARH) enough credit for everything it has done. But these things happened in Beckley, W.Va., right there at BARH. Not everyone knows that, but I think it’s important that they do.”

###

Cutline Information:

Photo 1: A group of original Beckley Miners Memorial Hospital employees pose for a photo just after the facility opened in 1956. Sally and John Ellison, who met at the hospital and married in 1957, are seen at the top left and right.

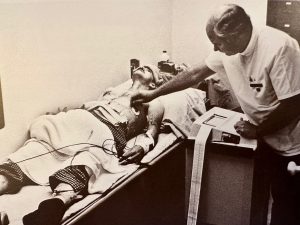

Photo 2: John Ellison performs an EKG on a coal miner at Beckley ARH Hospital.

Photo 3: Dr. Donald Rasmussen and John Ellison in the Beckley ARH Hospital pulmonary lab in later years.

# # #

Appalachian Regional Healthcare (ARH), is a not-for-profit health system operating 14 hospitals in Barbourville, Hazard, Harlan, Hyden, Martin, McDowell, Middlesboro, Paintsville, Prestonsburg, West Liberty, Whitesburg, and South Williamson in Kentucky and Beckley and Hinton in West Virginia, as well as multi-specialty physician practices, home health agencies, home medical equipment stores and retail pharmacies and medical spas. ARH employs approximately 6,700 people with an annual payroll and benefits of $474 million generated into our local economies. ARH also has a network of more than 1,300 providers on staff across its multi-state system. ARH is the largest provider of care and the single largest employer in southeastern Kentucky, and the third-largest private employer in southern West Virginia